Silk Road Trade & Travel Encyclopedia

丝绸之路网站(丝路网站)

丝绸之路百科全书—游客、学生和教师的参考资源

İPEK YOLU

ve YOLLARI

ANSİKLOPEDİSİ

一 To Start Your Silk Routes Journey

CLICK

on a Letter from the Alphabetical

Glossary

一

A B

C

D

E

F

G

H I

J

K

L

M

N O P

Q

R

S

T

U V

W

X

Y

Z

Demystifying the "Silk Road," the "Orient," and "Orientalism"

"The Silk Road" (click here for definition & use of term)

Brief definition: In 1877 the term "Seidenstraße" (literally "Silk Road") was coined by the German geographer, cartographer and explorer Ferdinand von Richthofen. It was 20 centuries after the first Chinese missions to the West, that the term "Silk Road" began to be used. The term now refers to the centuries-old trade network that has linked the Asian and Mediterranean worlds since antiquity (and often includes not only overland, but also maritime routes). The term "Silk Route(s)" is also used to describe the connection of trade routes that grew into an extensive Eurasian trans-continental network.

"Orientalist"

Brief definition: One who studies Oriental cultures (a.k.a. Oriental Studies).

"Orientalism"

Brief definition: The scholarly knowledge of Asian cultures, languages and people.

Orientalism has often been defined as the study of Near and Far Eastern societies and

cultures, by Westerners.

Orientalism is also a term used for the imitation or depiction of aspects of Eastern cultures in the West by writers and artists.

Orientalism refers to the Orient or East, in contrast to the Occident or West (from the Latin oriens: "Orient" is derived from the Latin word oriens meaning "east," used as the word for "rising" to refer to the east where the sun rises).

History of "Oriental" Studies

(Asian Studies - Central Asian Studies - Near

Eastern/Middle Eastern Studies - Post Colonial Studies - Eurasian

Studies)

Oriental studies is the academic field of study that embraces

Near

Eastern and

Far

Eastern societies and cultures, languages, peoples, history and

archaeology; in recent years the term

Asian studies has mostly replaced the older term.

More...

Since the 19th century, "Orientalist" has been the traditional term for a scholar of Oriental studies, however the use in English of "Orientalism" to describe academic "Oriental studies" is rare; the Oxford English Dictionary cites only one such usage, by Lord Byron in 1812. Orientalism was more widely used to refer to the works of French artists in the 19th century, who used artistic elements derived from their travels to non-European countries of North Africa and Western Asia.

It can be argued that the most readily accepted designation for Orientalism is an academic one, and indeed the label still serves in a number of academic institutions. Anyone who teaches, writes about, or researches the Orient (whether an anthropologist, sociologist, historian, or philologist) can be considered an Orientalist.

Nonetheless, the 20th century saw considerable change in the term's usage. In 1978, American-Palestinian scholar Edward Said published his influential and controversial book, Orientalism, in which he used the term to describe a pervasive Western tradition, both academic and artistic, of prejudiced outsider interpretations of the East, shaped by the attitudes of European imperialism in the 18th and 19th centuries. Said was critical of both this scholarly tradition and of some modern scholars, particularly Bernard Lewis. American literary critic Paul De Man supported Said's criticism of these modern scholars.

In complete contrast, some modern scholars have used the term to refer to writers of the Imperialist era with pro-Eastern attitudes.[2]

More recently, the term is also used in the meaning of "stereotyping of Islam", both by advocates and academics in refugee rights advocacy. A particular aspect of this stereotyping, described as "neo-Orientalism", occurs in the context of forced migration, particularly affecting women, and its alleged damage to refugee rights both in and outside the Arab and Muslim world.[3]

Meaning of the Term

Orientalism refers to the Orient or East,[4] in contrast to the Occident or West.

In the later Roman Empire, the Praetorian prefecture of the East, the Praefectura Praetorio Orientis, included most of the Eastern Roman Empire from the eastern Balkans eastwards; its easternmost part was the Diocese of the East, the Dioecesis Orientis, corresponding roughly to Greater Syria.

Over time, the common understanding of 'the Orient' has continually shifted eastwards, as Western explorers traveled farther into Asia. It finally reached the Pacific Ocean, in what Westerners came to call 'the Far East'. These shifts in time and identification sometimes confuse the scope (historical and geographic) of Oriental Studies.

Yet, there remain contexts where 'the Orient' and 'Oriental' have kept their older meanings, e.g. 'Oriental spices' typically are from the regions extending from the Middle East to sub-continental India to Indo-China. Travelers may again take the Orient Express train from Paris to Istanbul, a route established in the early 20th century. It never reached the nations bordering the Pacific Ocean, or what is currently understood to be the Orient.

In contemporary English, Oriental usually refers to goods from the parts of East Asia traditionally occupied by East Asians and most Central Asians and Southeast Asians racially categorized as "Mongoloid". This excludes Indians, Arabs, most other West Asian peoples. Because of historical discrimination against Chinese and Japanese, in some parts of the United States, the term is considered derogatory; for example, Washington state prohibits use of the word "Oriental" in legislation and government documentation, preferring the word "Asian" instead.[5]

Architecture

Early architectural use of motifs lifted from the Indian subcontinent have sometimes been called "Hindoo style". One of the earliest examples is the façade of Guildhall, London (1788–1789). The style gained momentum in the west with the publication of views of India by William Hodges, and William and Thomas Daniell from about 1795. One of the finest examples of "Hindoo" architecture is Sezincote House (c. 1805) in Gloucestershire. Other notable buildings in the Hindoo style of architecture are Casa Loma in Toronto, Sanssouci in Potsdam, and Wilhelma in Stuttgart.

Chinoiserie is the catch-all term for the fashion for Chinese themes in decoration in Western Europe, beginning in the late 17th century and peaking in waves, especially Rococo Chinoiserie, ca. 1740–1770. From the Renaissance to the 18th century, Western designers attempted to imitate the technical sophistication of Chinese ceramics with only partial success. Early hints of Chinoiserie appeared in the 17th century in nations with active East India companies: England (the British East India Company), Denmark (the Danish East India Company), Holland (the Dutch East India Company) and France (the French East India Company). Tin-glazed pottery made at Delft and other Dutch towns adopted genuine blue-and-white Ming decoration from the early 17th century. Early ceramic wares made at Meissen and other centers of true porcelain imitated Chinese shapes for dishes, vases and teawares. (See Chinese export porcelain)

Pleasure pavilions in "Chinese taste" appeared in the formal parterres of late Baroque and Rococo German palaces, and in tile panels at Aranjuez near Madrid. Thomas Chippendale's mahogany tea tables and china cabinets, especially, were embellished with fretwork glazing and railings, ca 1753–70. Sober homages to early Xing scholars' furnishings were also naturalized, as the tang evolved into a mid-Georgian side table and squared slat-back armchairs that suited English gentlemen as well as Chinese scholars. Not every adaptation of Chinese design principles falls within mainstream "chinoiserie." Chinoiserie media included imitations of lacquer and painted tin (tôle) ware that imitated japanning, early painted wallpapers in sheets, and ceramic figurines and table ornaments. Small pagodas appeared on chimneypieces and full-sized ones in gardens. Kew has a magnificent garden pagoda designed by Sir William Chambers.

After 1860, Japonisme, sparked by the importing of Japanese woodblock prints, became an important influence in the western arts. In particular, many modern French artists such as Monet and Degas were influenced by the Japanese style. Mary Cassatt, an American artist who worked in France, used elements of combined patterns, flat planes and shifting perspective of Japanese prints in her own images. The paintings of James McNeill Whistler and his "Peacock Room" demonstrated how he used aspects of Japanese tradition and are some of the finest works of the genre. California architects Greene and Greene were inspired by Japanese elements in their design of the Gamble House and other buildings.

Depictions of the Orient in art and literature

Depictions of Islamic "Moors" and "Turks" (imprecisely named Muslim groups of North Africa and West Asia) can be found in Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque art. In Biblical scenes in Early Netherlandish painting, secondary figures, especially Romans and Jews, were given exotic costumes that distantly reflected the clothes of the Near East. The Three Magi in Nativity scenes were an especial focus for this. Renaissance Venice had a phase of particular interest in depictions of the Ottoman Empire in painting; Gentile Bellini, who travelled to Constantinople and painted the Sultan, and Vittore Carpaccio were the leading exponents. By then the depictions were more accurate, with men typically dressed all in white. The depiction of Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting sometimes draws from Orientalist interest, but more often just reflects the prestige these expensive objects had in the period.

Turquerie, which began as early as the late 15th century, and continued until at least the 18th.

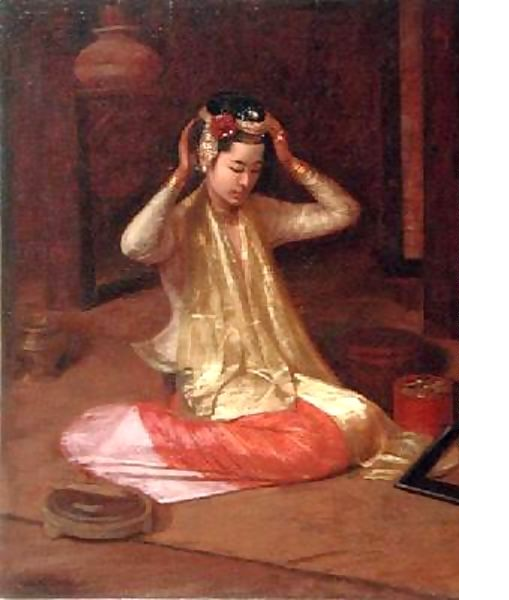

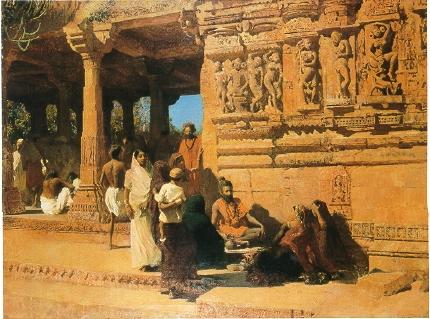

In the nineteenth century, when more artists traveled to the Middle East, they began representing more numerous scenes of Oriental culture. In many of these works, they portrayed the Orient as exotic, colorful and sensual. Such works typically concentrated on Near-Eastern Islamic cultures, as those were the ones visited by artists as France became more engaged in North Africa. French artists such as Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres painted many works depicting Islamic culture, often including lounging odalisques. They stressed both lassitude and visual spectacle. The later Russian artist Alexander Roubtzoff was also fascinated by what he saw on travels to Tunisia.

When Ingres, director of the French Académie de peinture, painted a highly colored vision of a turkish bath (illustration, right), he made his eroticized Orient publicly acceptable by his diffuse generalizing of the female forms (who might all have been the same model.) More open sensuality was seen as acceptable in the exotic Orient. This imagery persisted in art into the early 20th century, as evidenced in Matisse's Orientalist semi-nudes from his Nice period, and his use of Oriental costumes and patterns.

In his novel Salammbô, Gustave Flaubert used ancient Carthage in North Africa as a foil to ancient Rome. He portrayed its culture as morally corrupting and suffused with dangerously alluring eroticism. This novel proved hugely influential on later portrayals of ancient Semitic cultures.

The use of the orient as an exotic backdrop continued in the movies, for instance, those featuring Rudolph Valentino. Later the rich Arab in robes became a more popular theme, especially during the oil crisis of the 1970s. In the 1990s the Arab terrorist became a common villain figure in Western movies.